Apocalypse When? Hubble Casts Doubt on Certainty of Galactic Collision

As far back as 1912, astronomers realized that the Andromeda galaxy — then thought to be only a nebula — was headed our way. A century later, astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope were able to measure the sideways motion of Andromeda and found it was so negligible that an eventual head-on collision with the Milky Way seemed almost certain.

A smashup between our own galaxy and Andromeda would trigger a firestorm of star birth, supernovae, and maybe toss our Sun into a different orbit. Simulations had suggested it was as inevitable as, in the words of Benjamin Franklin, “death and taxes.”

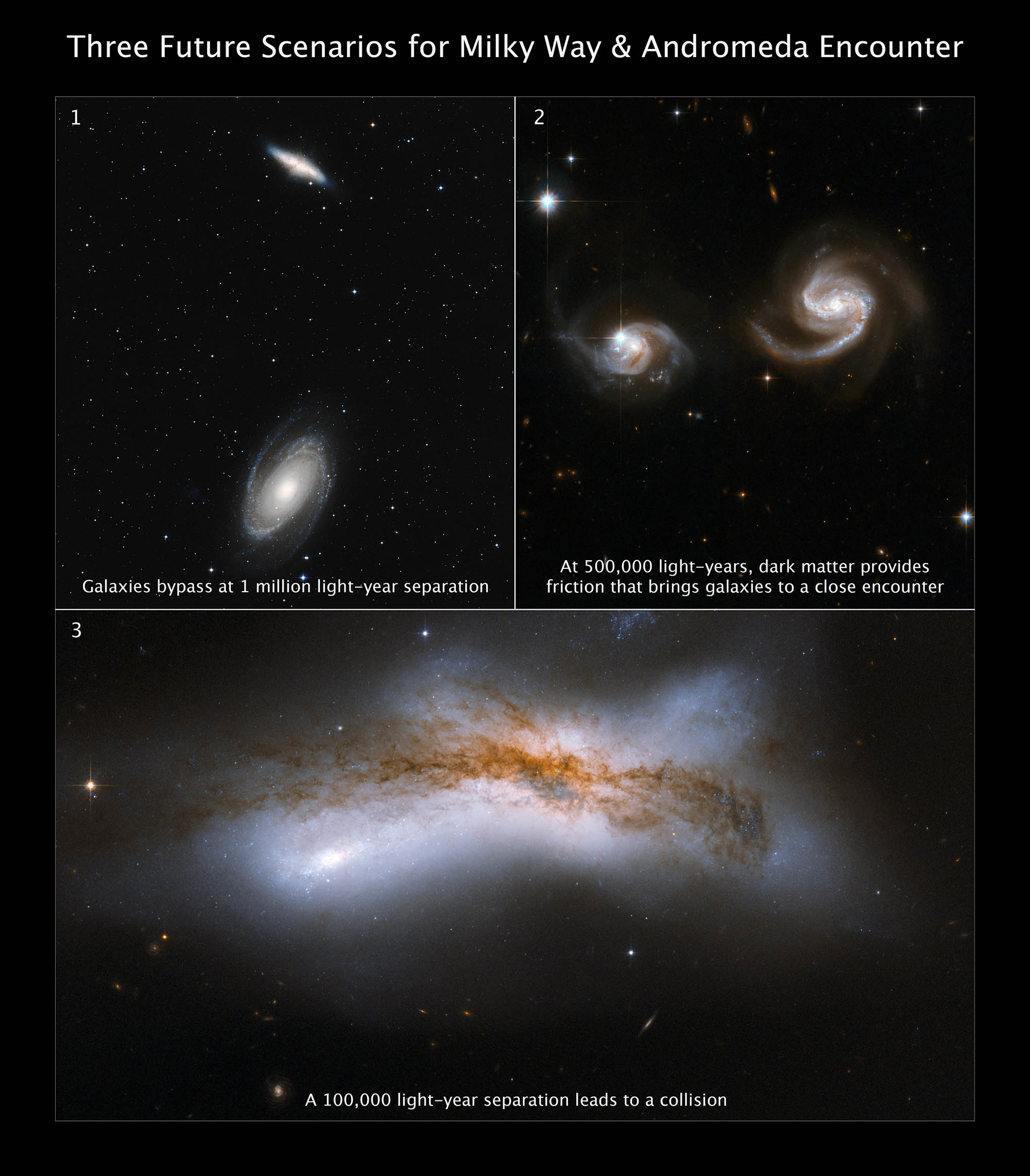

But now a new study using data from Hubble and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia space telescope says “not so fast.” Researchers combining observations from the two space observatories re-examined the long-held prediction of a Milky Way – Andromeda collision, and found it is far less inevitable than astronomers had previously suspected.

“We have the most comprehensive study of this problem today that actually folds in all the observational uncertainties,” said Till Sawala, astronomer at the University of Helsinki in Finland and lead author of the study, which appears today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

His team includes researchers at Durham University, United Kingdom; the University of Toulouse, France; and the University of Western Australia. They found that there is approximately a 50-50 chance of the two galaxies colliding within the next 10 billion years. They based this conclusion on computer simulations using the latest observational data.

Sawala emphasized that predicting the long-term future of galaxy interactions is highly uncertain, but the new findings challenge the previous consensus and suggest the fate of the Milky Way remains an open question.

“Even using the latest and most precise observational data available, the future of the Local Group of several dozen galaxies is uncertain. Intriguingly, we find an almost equal probability for the widely publicized merger scenario, or, conversely, an alternative one where the Milky Way and Andromeda survive unscathed,” said Sawala.

The collision of the two galaxies had seemed much more likely in 2012, when astronomers Roeland van der Marel and Tony Sohn of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland published a detailed analysis of Hubble observations over a five-to-seven-year period, indicating a direct impact in no more than 5 billion years.

“It’s somewhat ironic that, despite the addition of more precise Hubble data taken in recent years, we are now less certain about the outcome of a potential collision. That’s because of the more complex analysis and because we consider a more complete system. But the only way to get to a new prediction about the eventual fate of the Milky Way will be with even better data,” said Sawala.