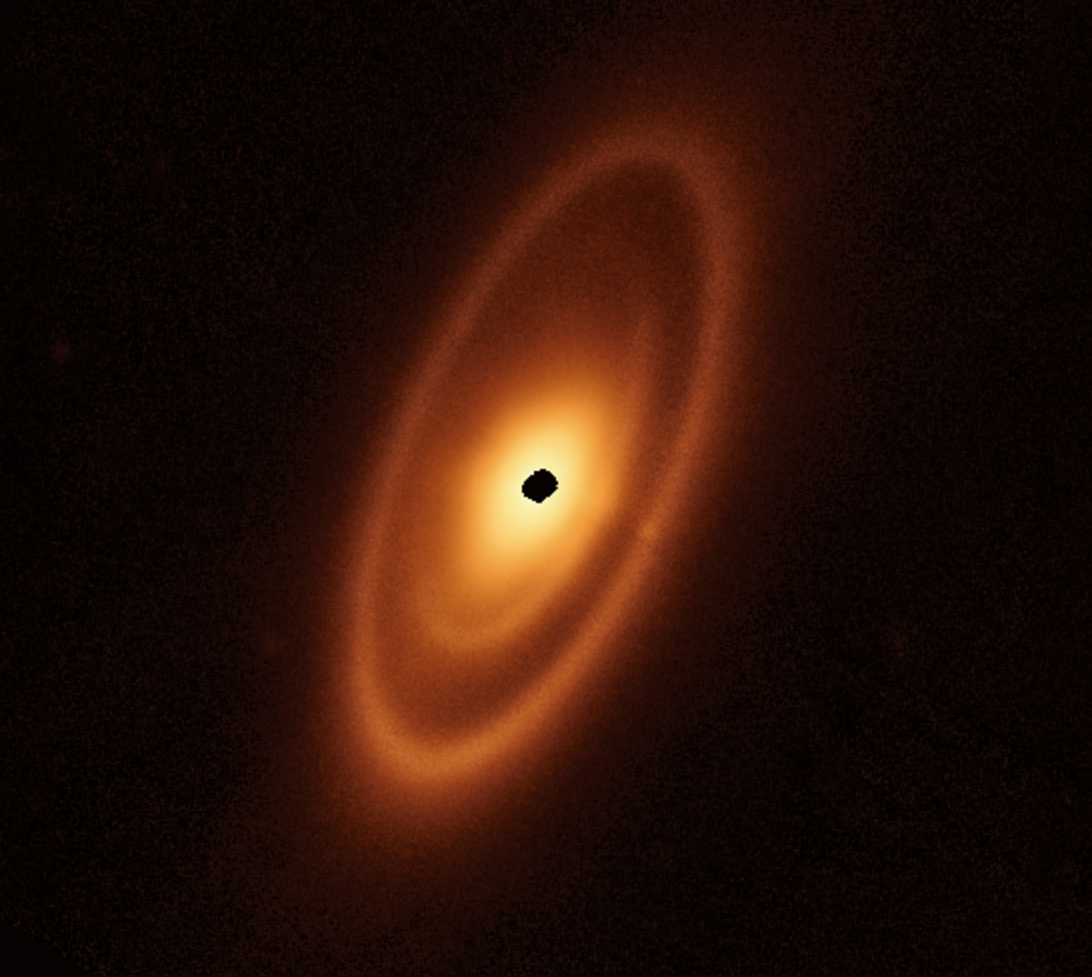

STScI: Webb Looks for Fomalhaut’s Asteroid Belt and Finds Much More

Astronomers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to image the warm dust around a nearby young star, Fomalhaut, in order to study the first asteroid belt ever seen outside of our solar system in infrared light. But to their surprise, the dusty structures are much more complex than the asteroid and Kuiper dust belts of our solar system. Overall, there are three nested belts extending out to 14 billion miles (23 billion kilometers) from the star; that’s 150 times the distance of Earth from the Sun. The scale of the outermost belt is roughly twice the scale of our solar system’s Kuiper Belt of small bodies and cold dust beyond Neptune. The inner belts – which had never been seen before – were revealed by Webb for the first time.

The belts encircle the young hot star, which can be seen with the naked eye as the brightest star in the southern constellation Piscis Austrinus. The dusty belts are the debris from collisions of larger bodies, analogous to asteroids and comets, and are frequently described as ‘debris disks.’ “I would describe Fomalhaut as the archetype of debris disks found elsewhere in our galaxy, because it has components similar to those we have in our own planetary system,” said András Gáspár of the University of Arizona in Tucson and lead author of a new paper describing these results. “By looking at the patterns in these rings, we can actually start to make a little sketch of what a planetary system ought to look like — if we could actually take a deep enough picture to see the suspected planets.”

The Hubble Space Telescope and the Herschel Space Observatory, as well as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), have previously taken sharp images of the outermost belt. However, none of them found any structure interior to it. The inner belts have been resolved for the first time by Webb in infrared light. “Where Webb really excels is that we’re able to physically resolve the thermal glow from dust in those inner regions. So you can see inner belts that we could never see before,” said Schuyler Wolff, another member of the team at the University of Arizona.

Hubble, ALMA, and Webb are tag-teaming to assemble a holistic view of the debris disks around a number of stars. “With Hubble and ALMA, we were able to image a bunch of Kuiper Belt analogs, and we’ve learned loads about how outer disks form and evolve,” said Wolff. “But we need Webb to allow us to image a dozen or so asteroid belts elsewhere. We can learn just as much about the inner warm regions of these disks as Hubble and ALMA taught us about the colder outer regions.”

These belts most likely are carved by the gravitational forces produced by unseen planets. Similarly, inside our solar system Jupiter corrals the asteroid belt, the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt is sculpted by Neptune, and the outer edge could be shepherded by as-yet-unseen bodies beyond it. As Webb images more systems, we will learn about the configurations of their planets.