STScI: NASA’s Webb Measures the Temperature of a Rocky Exoplanet

An international team of researchers has used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to measure the temperature of the rocky exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 b. The measurement is based on the planet’s thermal emission: heat energy given off in the form of infrared light detected by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). The result indicates that the planet’s dayside has a temperature of about 500 kelvins (roughly 450 degrees Fahrenheit) and suggests that it has no significant atmosphere.

This is the first detection of any form of light emitted by an exoplanet as small and as cool as the rocky planets in our own solar system. The result marks an important step in determining whether planets orbiting small active stars like TRAPPIST-1 can sustain atmospheres needed to support life. It also bodes well for Webb’s ability to characterize temperate, Earth-sized exoplanets using MIRI.

“These observations really take advantage of Webb’s mid-infrared capability,” said Thomas Greene, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and lead author on the study published today in the journal Nature. “No previous telescopes have had the sensitivity to measure such dim mid-infrared light.”

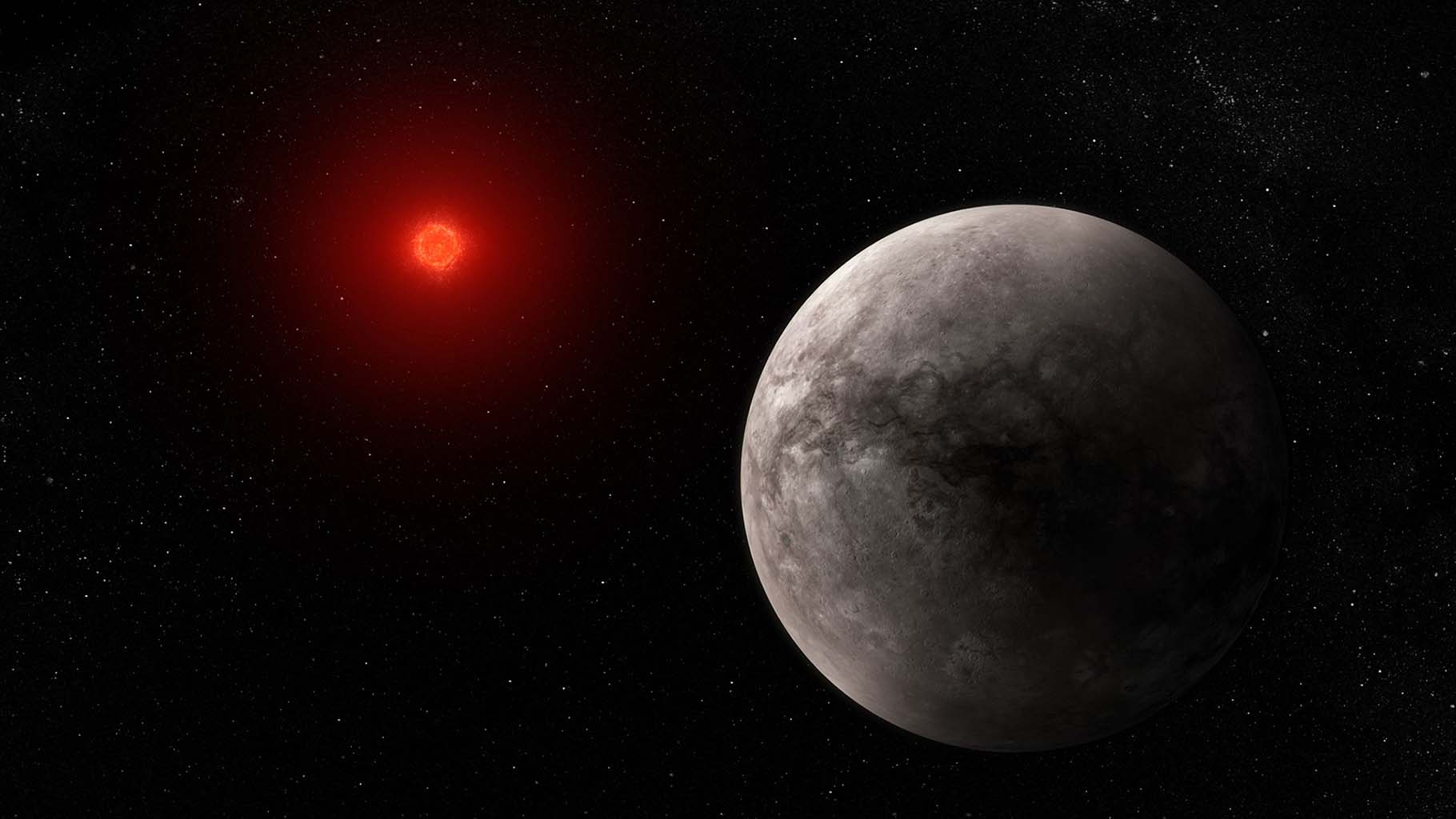

Rocky Planets Orbiting Ultracool Red Dwarfs

In early 2017, astronomers reported the discovery of seven rocky planets orbiting an ultracool red dwarf star (or M dwarf) 40 light-years from Earth. What is remarkable about the planets is their similarity in size and mass to the inner, rocky planets of our own solar system. Although they all orbit much closer to their star than any of our planets orbit the Sun — all could fit comfortably within the orbit of Mercury — they receive comparable amounts of energy from their tiny star.

TRAPPIST-1 b, the innermost planet, has an orbital distance about one hundredth that of Earth’s and receives about four times the amount of energy that Earth gets from the Sun. Although it is not within the system’s habitable zone, observations of the planet can provide important information about its sibling planets, as well as those of other M-dwarf systems.

“There are ten times as many of these stars in the Milky Way as there are stars like the Sun, and they are twice as likely to have rocky planets as stars like the Sun,” explained Greene. “But they are also very active — they are very bright when they’re young, and they give off flares and X-rays that can wipe out an atmosphere.”