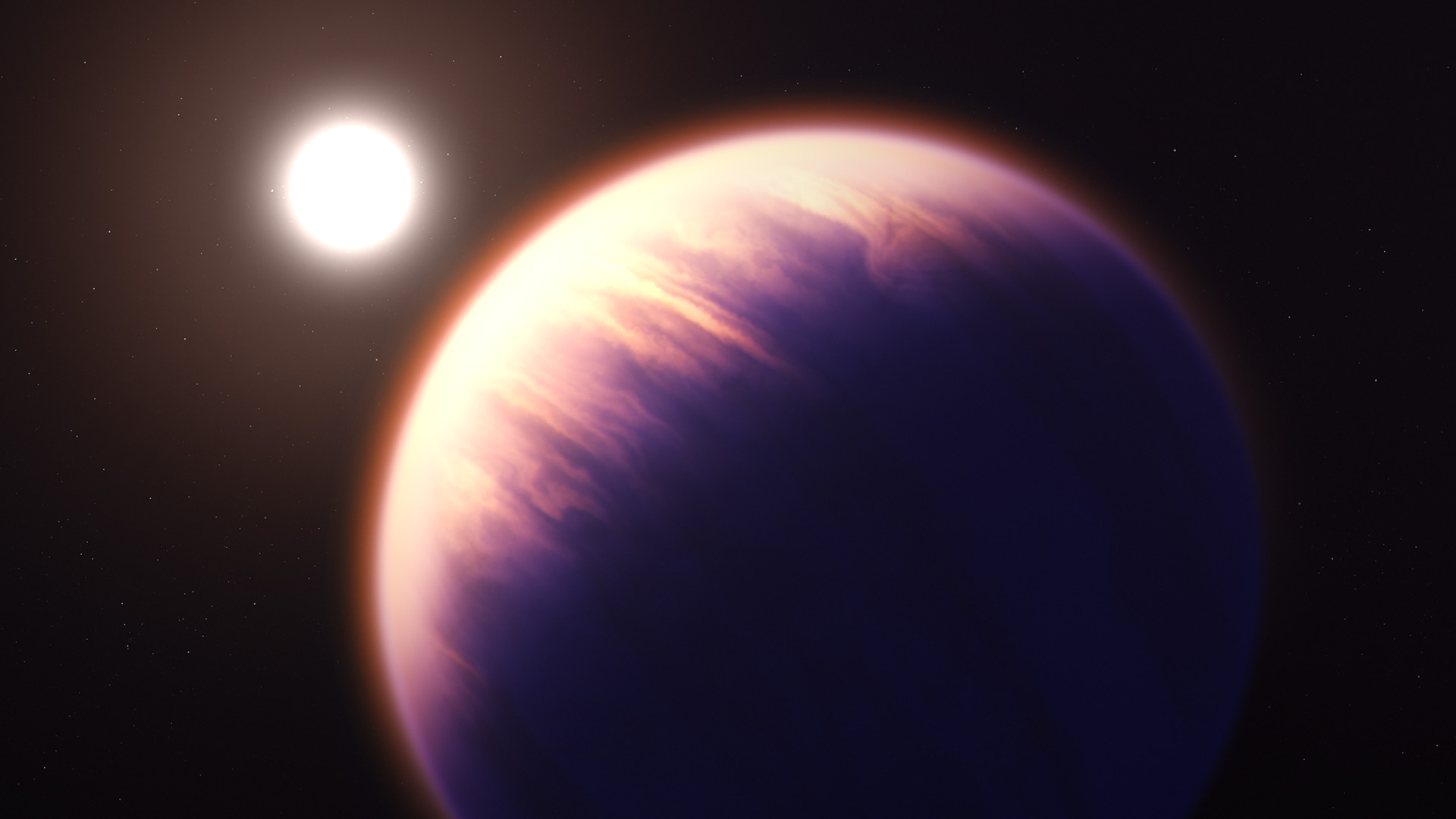

STScI: NASA’s Webb Reveals an Exoplanet Atmosphere as Never Seen Before

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope just scored another first: a molecular and chemical profile of a distant world’s skies.

While Webb and other space telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer, previously have revealed isolated ingredients of this broiling planet’s atmosphere, the new readings from Webb provide a full menu of atoms, molecules, and even signs of active chemistry and clouds.

The latest data also give a hint of how these clouds might look up close: broken up rather than a single, uniform blanket over the planet.

The telescope’s array of highly sensitive instruments was trained on the atmosphere of WASP-39 b, a “hot Saturn” (a planet about as massive as Saturn but in an orbit tighter than Mercury) orbiting a star some 700 light-years away.

The findings bode well for the capability of Webb’s instruments to conduct the broad range of investigations of all types of exoplanets – planets around other stars – hoped for by the science community. That includes probing the atmospheres of smaller, rocky planets like those in the TRAPPIST-1 system.

“We observed the exoplanet with multiple instruments that, together, provide a broad swath of the infrared spectrum and a panoply of chemical fingerprints inaccessible until [this mission],” said Natalie Batalha, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who contributed to and helped coordinate the new research. “Data like these are a game changer.”

The suite of discoveries is detailed in a set of five new scientific papers, three of which are in press and two of which are under review. Among the unprecedented revelations is the first detection in an exoplanet atmosphere of sulfur dioxide (SO2), a molecule produced from chemical reactions triggered by high-energy light from the planet’s parent star. On Earth, the protective ozone layer in the upper atmosphere is created in a similar way.

“This is the first time we see concrete evidence of photochemistry – chemical reactions initiated by energetic stellar light – on exoplanets,” said Shang-Min Tsai, a researcher at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and lead author of the paper explaining the origin of sulfur dioxide in WASP-39 b’s atmosphere. “I see this as a really promising outlook for advancing our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres with [this mission].”

This led to another first: scientists applying computer models of photochemistry to data that requires such physics to be fully explained. The resulting improvements in modeling will help build the technological know-how to interpret potential signs of habitability in the future.