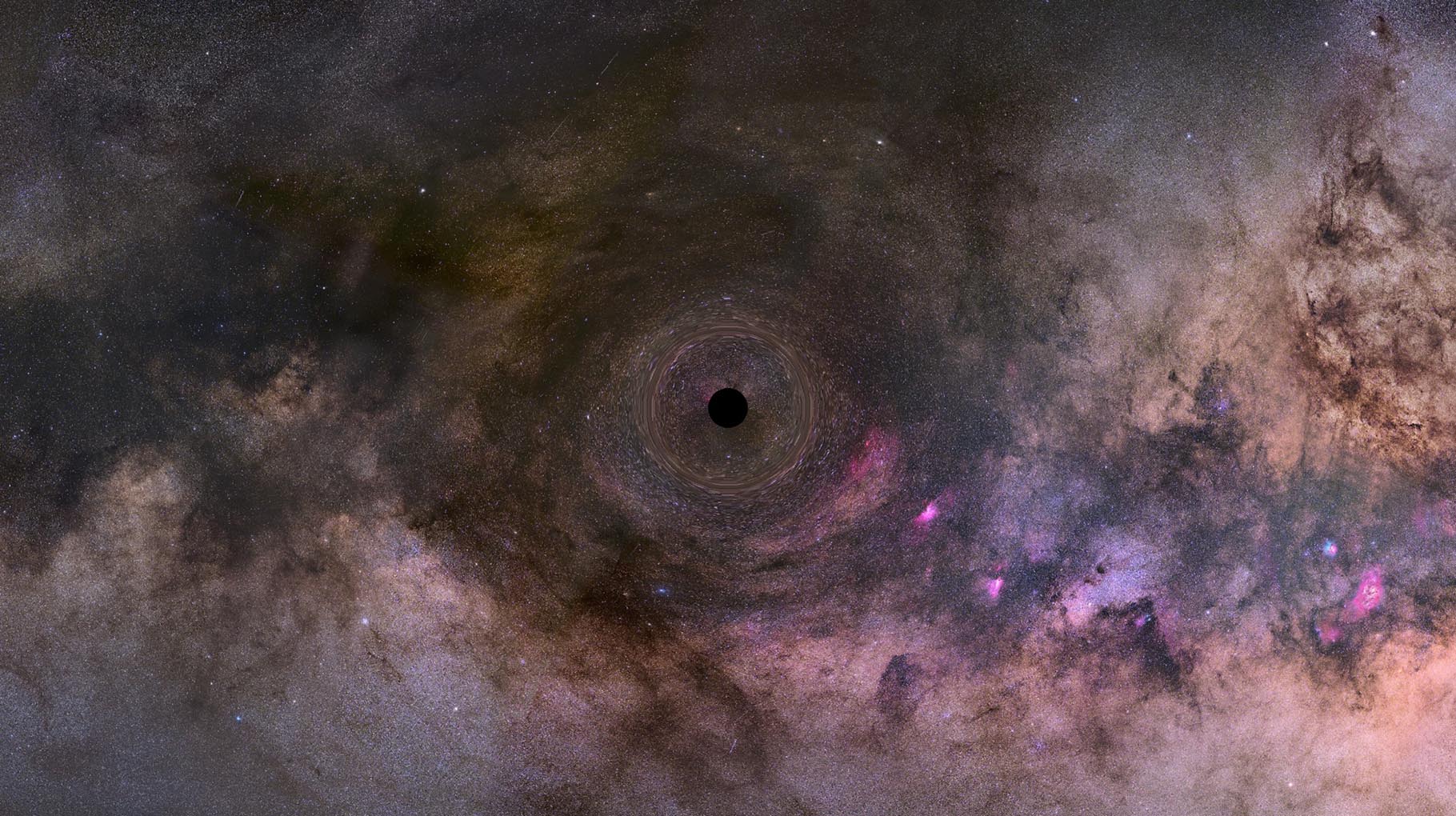

STScI: Hubble Determines Mass of Isolated Black Hole Roaming Our Milky Way Galaxy

Astronomers estimate that 100 million black holes roam among the stars in our Milky Way galaxy, but they have never conclusively identified an isolated black hole. Following six years of meticulous observations, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has, for the first time ever, provided direct evidence for a lone black hole drifting through interstellar space by a precise mass measurement of the phantom object. Until now, all black hole masses have been inferred statistically, or through interactions in binary systems or in the cores of galaxies. Stellar-mass black holes are usually found with companion stars, making this one unusual.

The newly detected wandering black hole lies about 5,000 light-years away, in the Carina-Sagittarius spiral arm of our galaxy. However, its discovery allows astronomers to estimate that the nearest isolated stellar-mass black hole to Earth might be as close as 80 light-years away. The nearest star to our solar system, Proxima Centauri, is a little over 4 light-years away.

Black holes roaming our galaxy are born from rare, monstrous stars (less than one-thousandth of the galaxy’s stellar population) that are at least 20 times more massive than our Sun. These stars explode as supernovae, and the remnant core is crushed by gravity into a black hole. Because the self-detonation is not perfectly symmetrical, the black hole may get a kick, and go careening through our galaxy like a blasted cannonball.

Telescopes can’t photograph a wayward black hole because it doesn’t emit any light. However a black hole warps space, which then deflects and amplifies starlight from anything that momentarily lines up exactly behind it.

Ground-based telescopes, which monitor the brightness of millions of stars in the rich star fields toward the central bulge of our Milky Way, look for a tell-tale sudden brightening of one of them when a massive object passes between us and the star. Then Hubble follows up on the most interesting such events.

Two teams used Hubble data in their investigations — one led by Kailash Sahu of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland; and the other by Casey Lam of the University of California, Berkeley. The teams’ results differ slightly, but both suggest the presence of a compact object.

The warping of space due to the gravity of a foreground object passing in front of a star located far behind it will momentarily bend and amplify the light of the background star as it passes in front of it. Astronomers use the phenomenon, called gravitational microlensing, to study stars and exoplanets in the approximately 30,000 events seen so far inside our galaxy.