NOIRLab: Are We Missing Other Earths?

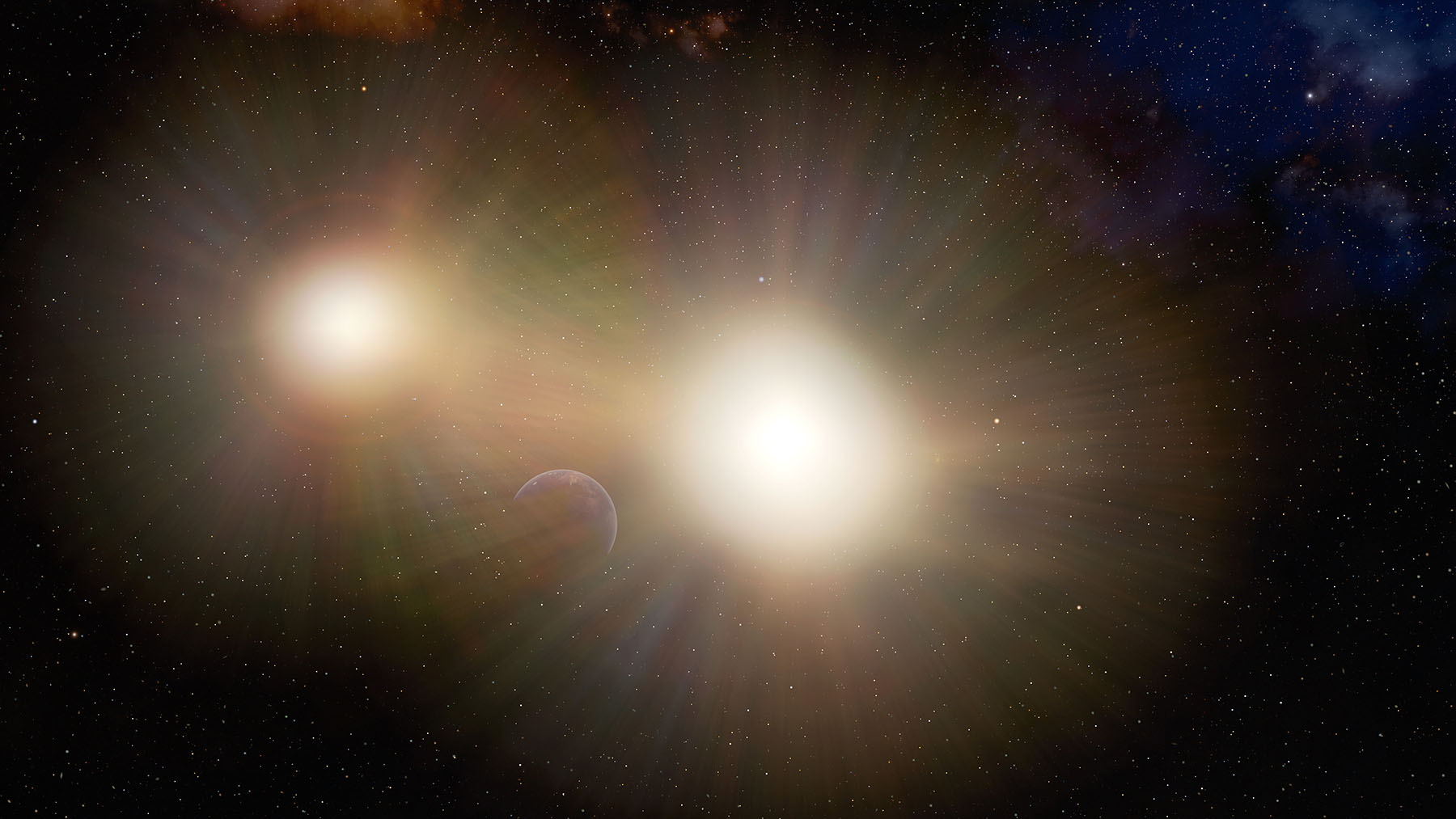

This illustration depicts a planet partially hidden in the glare of its host star and a nearby companion star. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva (Spaceengine)

Some exoplanet searches could be missing nearly half of the Earth-sized planets around other stars. New findings from a team using the international Gemini Observatory and the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory suggest that Earth-sized worlds could be lurking undiscovered in binary star systems, hidden in the glare of their parent stars. As roughly half of all stars are in binary systems, this means that astronomers could be missing many Earth-sized worlds.

Earth-sized planets may be much more common than previously realized. Astronomers working at NASA Ames Research Center have used the twin telescopes of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, to determine that many planet-hosting stars identified by NASA’s TESS exoplanet-hunting mission [1]are actually pairs of stars — known as binary stars — where the planets orbit one of the stars in the pair. After examining these binary stars, the team has concluded that Earth-sized planets in many two-star systems might be going unnoticed by transit searches like TESS’s, which look for changes in the light from a star when a planet passes in front of it [2]. The light from the second star makes it more difficult to detect the changes in the host star’s light when the planet transits.

The team started out by trying to determine whether some of the exoplanet host stars identified with TESS were actually unknown binary stars. Physical pairs of stars that are close together can be mistaken for single stars unless they are observed at extremely high resolution. So the team turned to both Gemini telescopes to inspect a sample of exoplanet host stars in painstaking detail. Using a technique called speckle imaging [3], the astronomers set out to see whether they could spot undiscovered stellar companions.

Using the `Alopeke and Zorro instruments on the Gemini North and South telescopes in Chile and Hawai‘i, respectively, [4] the team observed hundreds of nearby stars that TESS had identified as potential exoplanet hosts. They discovered that 73 of these stars are really binary star systems that had appeared as single points of light until observed at higher resolution with Gemini. “With the Gemini Observatory’s 8.1-meter telescopes, we obtained extremely high-resolution images of exoplanet host stars and detected stellar companions at very small separations,” said Katie Lester of NASA’s Ames Research Center, who led this work.

Lester’s team also studied an additional 18 binary stars previously found among the TESS exoplanet hosts using the NN-EXPLORE Exoplanet and Stellar Speckle Imager (NESSI) on the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, also a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab.